I’ve always been fascinated by the parallels and relationships between stories of different cultures. Here I’ll briefly, perhaps poetically, examine two stories from “cousin cultures” of the ancient world: the Epic of Gilgamesh, which is at least 4.000 years old and comes from ancient Mesopotamia; and the garden story from the biblical book of Genesis, which dates from around 2.500-2.900 years ago and is almost certainly based on older sources. Perhaps the most well-known parallel between these two tales deals with the Flood; however, here, we’ll look at something else.

There is a god, and eternal life, and a serpent.

In one story, you are created from clay in the garden of the gods, there to dwell peacefully within that place and care for it.

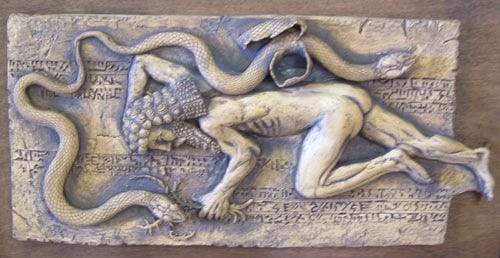

Later, there is sweat and travail, and a blooming chance at infinity — and a serpent snatches it away.

After the Great Flood, the god-chosen survivor is rewarded with eternal life for his troubles. Having heard of this, you, after much toil and much difficulty and loss, arrive to ask him for the key to immortality.

The test: you must defy sleep for six days and seven nights. You fail.

In consolation he tells you that there is a flower in the garden at the bottom of the waters of the world, a garden that was once a paradise and is now hidden under the remants of the Flood. In that place grows a flower which, while it cannot bestow immortality precisely, may grant a return to youth, eternally.

You risk it all to find that flower and bring it back, only for a serpent to steal it and leave you bereft.

In another story, you are created from the dust of the earth and placed in a garden, there to live in a state of nature with the rest of the garden’s inhabitants.

A god grants eternal life, and forbids ultimate knowledge; a serpent offers a tempting alternative.

Long before the Great Flood, in a garden, two trees grow: the tree of life and the tree of knowledge (the ultimate knowledge that confers a death of a sort: the death of unity, and the creation of the separate self).

The test: the tree of life is fair game, but of the particular fruit of the tree of knowledge, God has forbidden you to eat.

Like any child, you reach for that which has been forbidden: enticed, you devour that particular prohibited fruit, tempted to transgression by a serpent, that timeless trickster.

God condemns you for this, thrusting you from paradise and eternal life, and leaving you bereft.

There is much, much more to say, and many have indeed written much on the comparative mythology of Mesopotamia and its neighbors. The very name Eden may derive, in fact, from a Sumerian word, edin, meaning “steppe” or “plain”, or it may derive from a Hebrew word ultimately meaning “paradise”. The word “paradise” itself comes from a root meaning “walled garden”.

We can dance in this multiplicity of meaning: the garden, walled off from the surrounding wilds, is a haven of pleasure.

The Mesopotamian garden was a playground for the gods, and humanity was created to help steward and tend this garden for the pleasure of the gods. In the Genesis narrative, the garden was created for God and company to enjoy, for Adam and Eve to enjoy, for eternity — eternity, that is, until the humans took too great a liberty.

The blessed earth from which we were made is now cursed by God in our name for our blunder. This blessed earth is meant to become a bane to us: ours is no longer an innocent and infinite life walled off from the wilderness; now it is to us to toil for a living as we go out into the wider world. Thenceforth humans must procreate and struggle against the elements in order to ensure our survival and thriving, for, after all, now death is part of our life.

From blessed earth were we formed, and indeed, to blessed earth shall we return.

In both stories, some form of eternity was within reach: the flower of youth, or the tree of everlasting life. In both stories, the serpent was the messenger: your life must end, eventually. The serpent took the flower of rejuvenation from you, shedding his skin as he went and leaving you to age and die; or the serpent made sure the forbidden fruit was so appealing that your choice, and its consequences, would lead to eventual death.

To live, and love, and enjoy, day and night and night and day; to fully embrace the joys and pains of being alive: this is the simpleton's way, and this is the way of the sage.

Before enlightenment: chop wood, carry water.

After enlightenment: chop wood, carry water.

But before, we do not realize the strength of that wood, the weight of that water, the price of that fruit.

Once we know; once we have plunged to the depths of the world in search of that eternal flower; once we have tasted the fruit of the tree of truth; we realize the weight, and the burden becomes almost unbearable.

Partially inspired by this lovely article by .